Dietary Guidelines, Fiber, and the Microbiome: Progress Made, Precision Still Needed

By Steve Imgrund, LDN,

Marketing and Communications Lead, GPA

Why Gut Health Matters in the New Dietary Guidelines

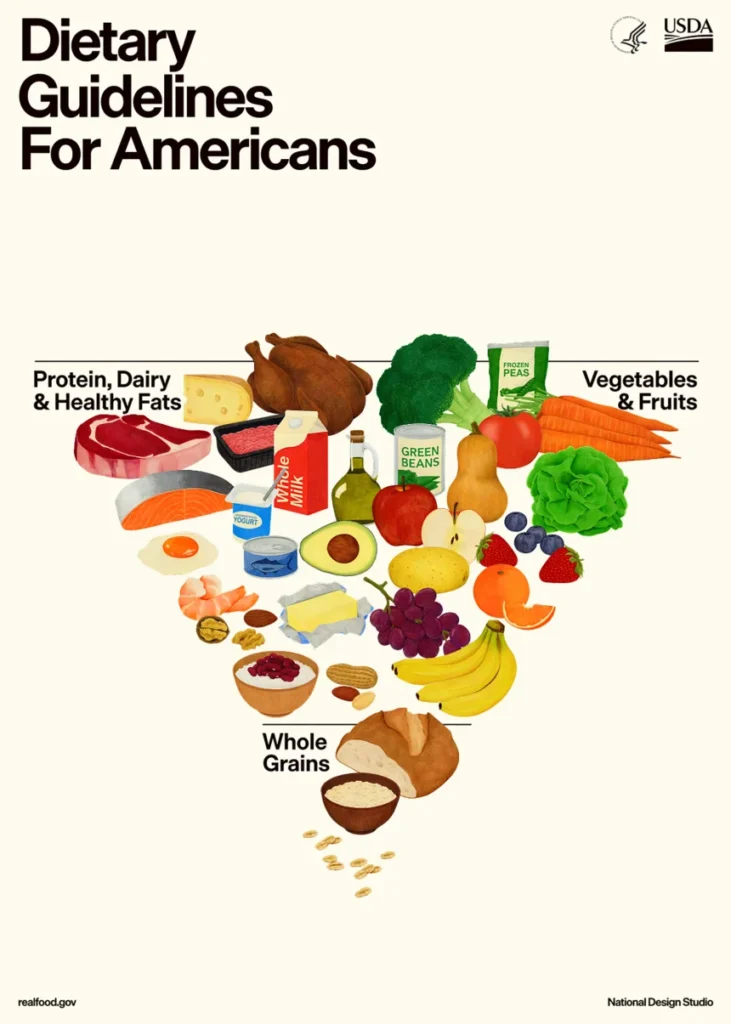

The recent release of new US dietary guidelines has sparked ongoing debate online about the correct interpretation and how this relates to realistic implementation. Some people see progress in the guidelines’ focus on whole foods, the clear advice to avoid highly processed foods, and the first-time recognition of the gut microbiome’s importance for overall health. From the perspective of the Global Prebiotics Association (GPA), which serves as a steward of the prebiotic category, these are meaningful and welcome developments.

Others point out that the guidelines lack specific, measurable recommendations, especially for fiber, as well as other concerns, including dairy recommendations, protein quality nuances, and more. There are certainly other valid criticisms of the guidelines, and as a licensed nutritionist working both in clinical practice and my role with the GPA, I see both sides: the importance of sound population guidance and the need to avoid rigid prescriptions that fail to account for biological variability.

Perhaps one of the bigger issues is that while guidelines do acknowledge the microbiome, treating fiber as a single category is inconsistent with that understanding. This is inconsistent with the growing body of evidence showing that different fibers, including those with prebiotic activity, have distinct, sometimes very different, effects across gut and metabolic health, as well as individual tolerance to those fiber types. Importantly, not all fiber functions as a prebiotic, and not all compounds with prebiotic activity are classified as fiber. Given the central role fiber plays in shaping the microbiome, it is notable that fiber is not discussed with the same familiarity or nuance as other macronutrients, such as protein, within the guidelines.

Why the Guidelines Avoid Rigid Fiber Targets

My interpretation of why we don’t see specific, quantifiable recommendations for things like fiber is that individual responses to both fiber and prebiotics vary widely. As a result, population-level guidance needs to remain broadly applicable. For example, individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may not tolerate many types of fiber, and in these cases, individualized dietary interventions are often necessary to manage symptoms while still supporting microbiome diversity and gut integrity.

At the same time, acknowledging this variability does not mean all fibers should be treated as equal. Added nuance around different fiber types, including those with prebiotic activity, is not the same as prescribing rigid intake mandates. So while the guidelines represent a meaningful step forward at the population level, by emphasizing whole foods and vegetables and calling out fermented foods as supportive of microbiome health, one-size-fits-all intake levels may do more harm than good for certain populations.

Clarifying Fiber, Prebiotic Activity, and Gut Health

Coming back to missed opportunities, future dietary guidance should look less like precise fiber intake prescriptions, and more about bringing more clarity around what “fiber” represents from a gut health perspective. While fiber is often discussed as a single nutrient category, it encompasses a wide range of compounds with different physiological roles. Some fibers primarily support GI function through effects on bulking stool and transit time, while others interact more directly with the gut microbiome through fermentation.

This distinction is particularly relevant when considering prebiotic activity. As outlined in the scientific consensus definition published by the Global Prebiotics Association, prebiotics are a compound or ingredient that is utilized by the microbiota, producing a health or performance benefit. Importantly, not all fibers meet this definition, and prebiotic activity is not limited exclusively to fiber. Certain non-fiber compounds, including specific polyphenols naturally present in fruits, vegetables, and other plant foods, have also been shown to influence microbial composition and activity in ways consistent with prebiotic effects.¹

Recognizing these functional differences does not require rigid intake targets or complex prescriptions. Rather, it provides clarity on how different plant-based foods can support gut health through distinct mechanisms. One practical example is carbohydrate processing: while the guidelines appropriately caution against highly refined foods, processing can also remove beneficial components such as resistant starch, an important fermentable substrate that historically contributed meaningfully to human diets but is now largely diminished in modern food systems. A more nuanced framework would acknowledge not only what is removed during processing, but also which functional components may be worth preserving or reintroducing. By more clearly differentiating between fiber’s structural roles in digestion and its functional roles in shaping the microbiome, including prebiotic activity, dietary guidance could better reflect current gut health science while keeping the flexibility necessary for population-level recommendations.

Fermented Foods: Progress Without Precision

One of the more encouraging updates in the new Dietary Guidelines is the inclusion of fermented foods as part of a dietary pattern that supports gut and microbiome health. This reflects a growing recognition that health is influenced not only by nutrients, but also by the microbial exposures that come from food. Fermented foods have long been part of traditional diets, and their inclusion signals a broader understanding of how diet can shape microbial diversity and function.

Beyond their cultural relevance, fermented foods are biologically distinct from other whole foods. A recent scientific review highlights that fermented foods can deliver a combination of live microorganisms, fermentation-derived metabolites, and bioactive compounds that interact with the gut ecosystem in ways that differ from fiber alone. Depending on the food and fermentation process, these effects may include probiotic, prebiotic-like, and postbiotic activity, all of which can influence microbial composition, immune signaling, and metabolic pathways in the host. Importantly, these effects vary widely across fermented foods, reflecting differences in substrates, microbial communities, and processing methods.²

As with fiber recommendations, the new dietary guidelines stop short of providing specific guidance on fermented food intake, such as recommended frequency or serving size. From an individualized nutrition perspective, this flexibility allows for personal/cultural preference and tolerance. At the same time, the lack of detail makes implementation more challenging at scale.

Looking Ahead

Taken together, the new Dietary Guidelines represent a meaningful shift in how nutrition guidance approaches gut health. The recognition of the microbiome, the emphasis on whole foods, fiber-rich diets, and the inclusion of fermented foods all signal progress. At the same time, these updates highlight an ongoing tension that’s common with population-level guidance: the need to balance clarity with flexibility in the face of bio-individuality.

From the perspective of the GPA, while not seeking perfection, future iterations of the guidelines present an opportunity to more clearly address the current fiber gap in the population’s dietary intake. Providing clearer details on how different dietary components support gut health through distinct mechanisms, along with identifying food sources and practical strategies to maintain or reintroduce functionally important fibers, would strengthen the guidance. This includes acknowledging how modern food processing has reduced exposure to certain compounds, such as resistant starch, without relying on rigid intake metrics.

Ultimately, dietary guidance will always serve as a starting point, not a prescription. We believe this represents progress, but also challenges with implementation at scale. There are many other aspects of the new guidelines that warrant discussion beyond the scope of this microbiome-focused piece. Still, their release creates an important opportunity to advance more nuanced, evidence-based conversations about gut health, the importance of a healthy microbiome and personalized nutrition. The Global Prebiotic Association supports those conversations as it continues to promote the responsible, evidence-based growth of the prebiotic category.

References:

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2161831324001637

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12056253/